After just a few days in Buenos Aires, I learned to tell the 96 bus apart from the 98 by their colors, but I still had to step out into the middle of the street to squint for the orange placard with a letter “S” indicating “semirápido,” meaning express. Although several Line 96 buses passed by every hour, only the semirápido towards Pontevedra got me where I needed to go, and those seemed to be the least common. Thankfully, I usually had several podcasts lined up and a set of Spanish flashcards in my bag to keep me entertained. On a good day, I left my apartment at 10:00 a.m. and reached CONIN Merlo, a center for malnourished children and a local chapter of Fundación CONIN, by 12:30 p.m. I had known what I was signing up for when I had booked an Airbnb so far from the center, but I had no other choice. It seemed that there was no safe place to live within two hours of the center on public transit. It didn’t dawn on me until later that the trains had been designed to section off that run-down and malnourished neighborhood from its more affluent neighbors. Though less obvious than Rio De Janeiro’s “wall of shame,” Buenos Aires had its own way of dividing the poor from the rich: public transit.

When I started planning for my internship last summer at Fundación CONIN, I noted with satisfaction that the Línea Belgrano Sur train passed within a short walk of the center and decided to look for apartments along that train line. Unfortunately, the Airbnb map seemed strangely empty around that area. As I started to research the neighborhoods surrounding the Línea Belgrano Sur, I came across urban-legend-style maps with labels like “don’t go here,” “Mordor,” “why would you even go here?,” “The hunger games,” “Say ‘bye bye’ to your life,” and “cross this river and you are dead.” It didn’t take long to get the idea that I would have to live somewhere else. To my chagrin, I realized that I couldn’t even live downtown and commute on the train because the Línea Belgrano Sur did not connect to the subway system. My only remaining option was two hours on the 96 express bus, then connecting at Pontevedra to the 236 or the 500.

I did eventually get a chance to ride the Línea Belgrano Sur, and—primed as I was by one year at Columbia University thinking about health inequities—a bullet hole in the window finally led me to realize what was going on. The Línea Belgrano Sur connects only the poor neighborhoods together.

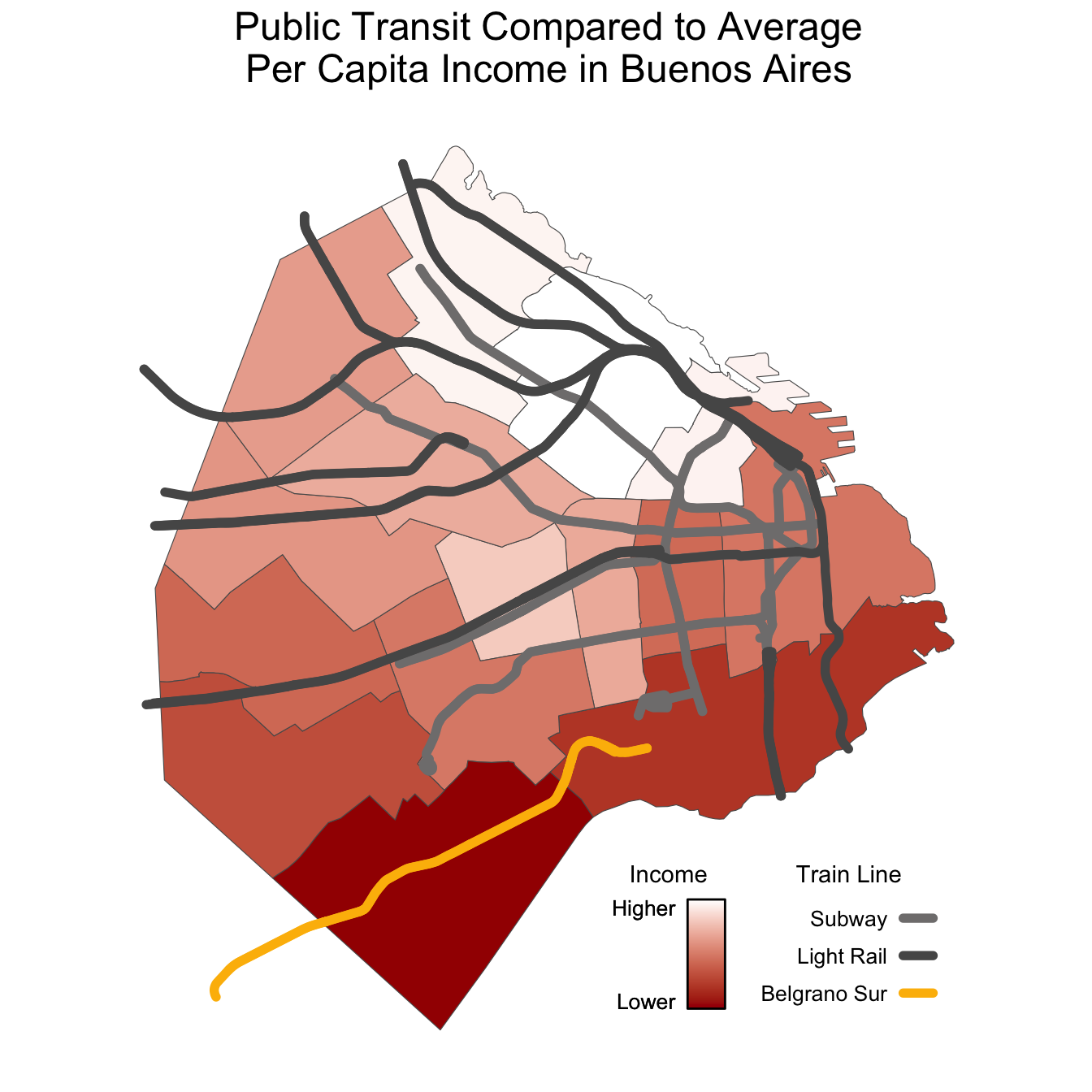

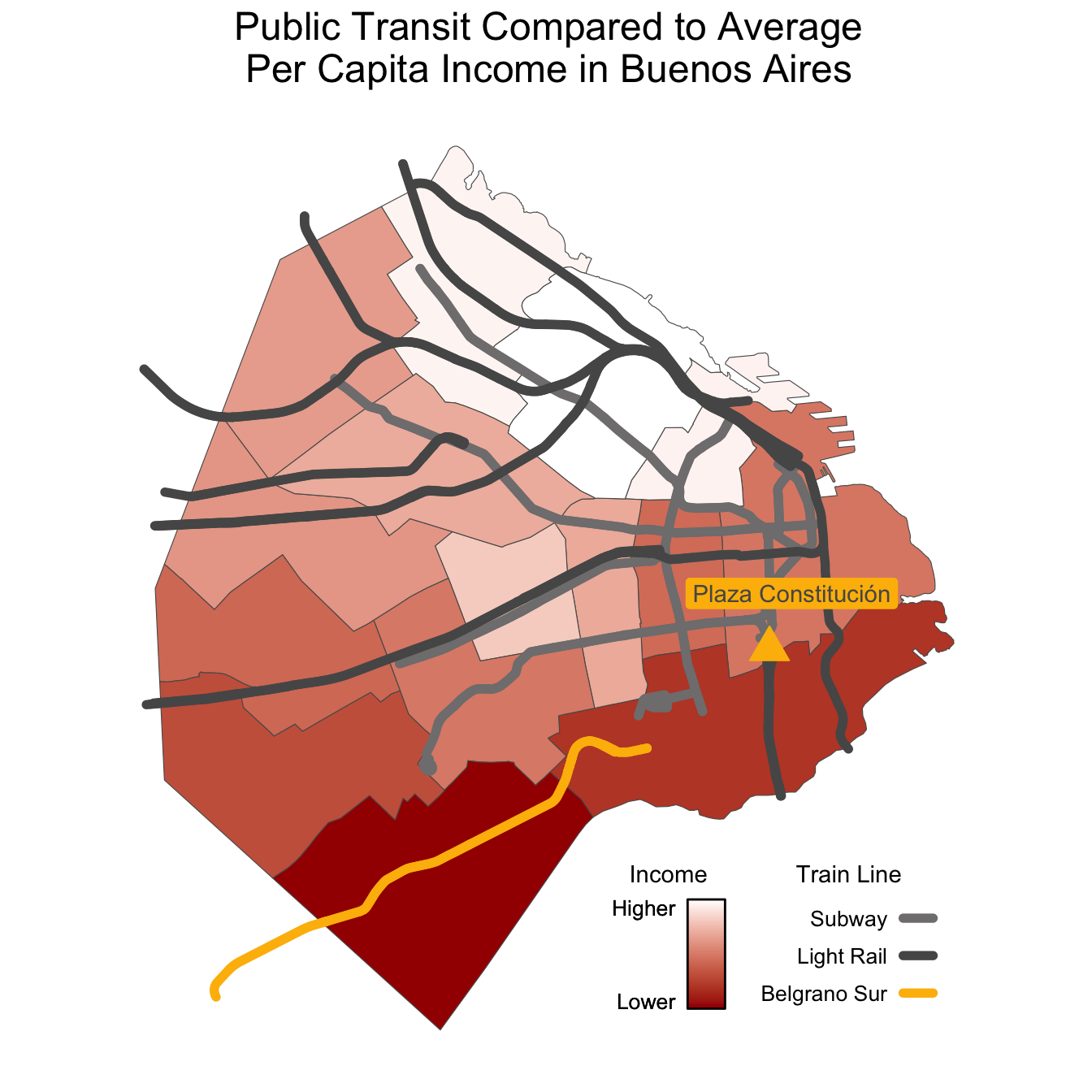

Curious to see if data would corroborate my impression, I found some income data for the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires, and I overlaid a train map. The center where I was volunteering was actually outside the boundaries of the City of Buenos Aires, and the plot below shows only as far out as the city limits, but even this zoomed-in snapshot paints a pretty clear picture. The train going through the lowest-income neighborhoods in the city is completely disconnected from the rest of the train system.

It would seem that the Línea Belgrano Sur is a neglected part of the system, just like the people who live near it. Like other systemic inequities, this one has surely been perpetuated over many years. I don’t know the whole storied history of the Línea Belgrano Sur, but one interesting tidbit of history is that, during the 80s, the last dictatorship tried to shut it down. They claimed that the train’s small ridership could be absorbed by the bus system, and they even put into service a replacement bus line running parallel to the track. Maybe the train did have a “small” ridership, but what I know about history leads me to call into question any plan to shut down critical infrastructure in a disadvantaged neighborhood.

Thankfully, the plans to shut the line down never came to fruition, and today things are starting to look better. Despite the fact that the Línea Belgrano Sur continues to run on diesel, unlike the nearby Línea Sarmiento which has been modernized to use electric motors, 65,000 people ride the train each day in relative comfort. In fact, if you get on the Línea Belgrano Sur today, it might seem pretty nice. Over the last few years, the government has poured money into the line, and in 2021, the government announced plans to extend the train line to Plaza Constitución, one of the nearest subway stations. Since assuming office last year, President Milei has ruthlessly cut funding to public projects, but it seems this one survived at least as long as the beginning of the year. A report at the end of January announced that the project was nearing completion. It seems there may still be hope for the Línea Belgrano Sur.

The interior of Línea Belgrano Sur on a rainy spring day.

The interior of Línea Belgrano Sur on a rainy spring day.

Work is almost complete to extend the Línea Belgrano Sur to Plaza Constitución

Data sources:

Income data from 2022 from MAPA PyD, a project by ICIUDAD and Defensoría Del Pueblo. https://www.iciudad.org.ar/georeferenciacion/resultados/Indicadores%20PyD%20-%202022.pdf

Rail and Subway GIS data from Overpass Turbo. https://overpass-turbo.eu

Photography by Nicolás Roldán